Reliability and Resiliency for Cloud Connected Applications

/Building cloud connected applications that are reliable is hard. At the heart of building such a system is a solid architecture and focus on resiliency. We're going to explore what that means in this post.

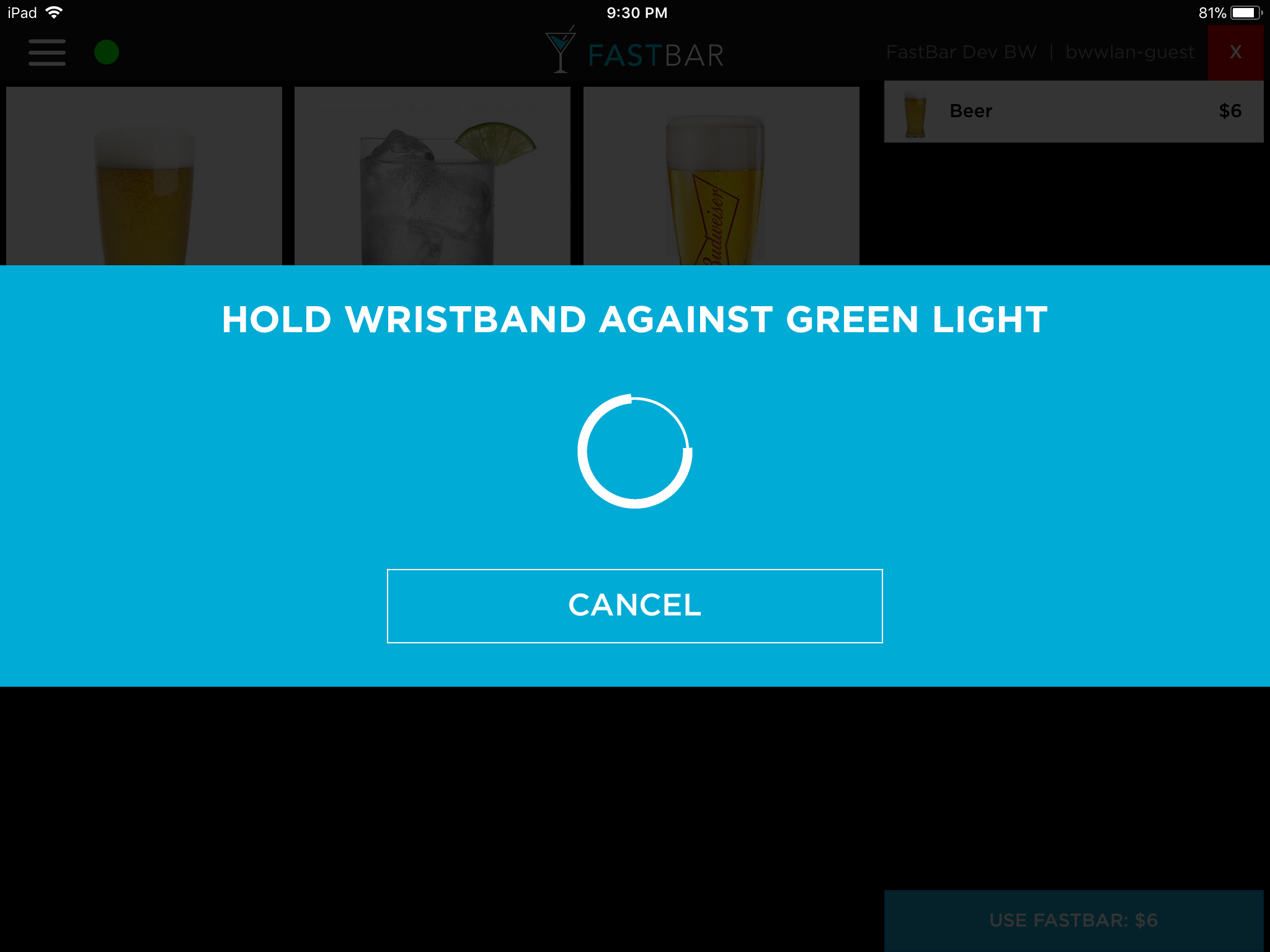

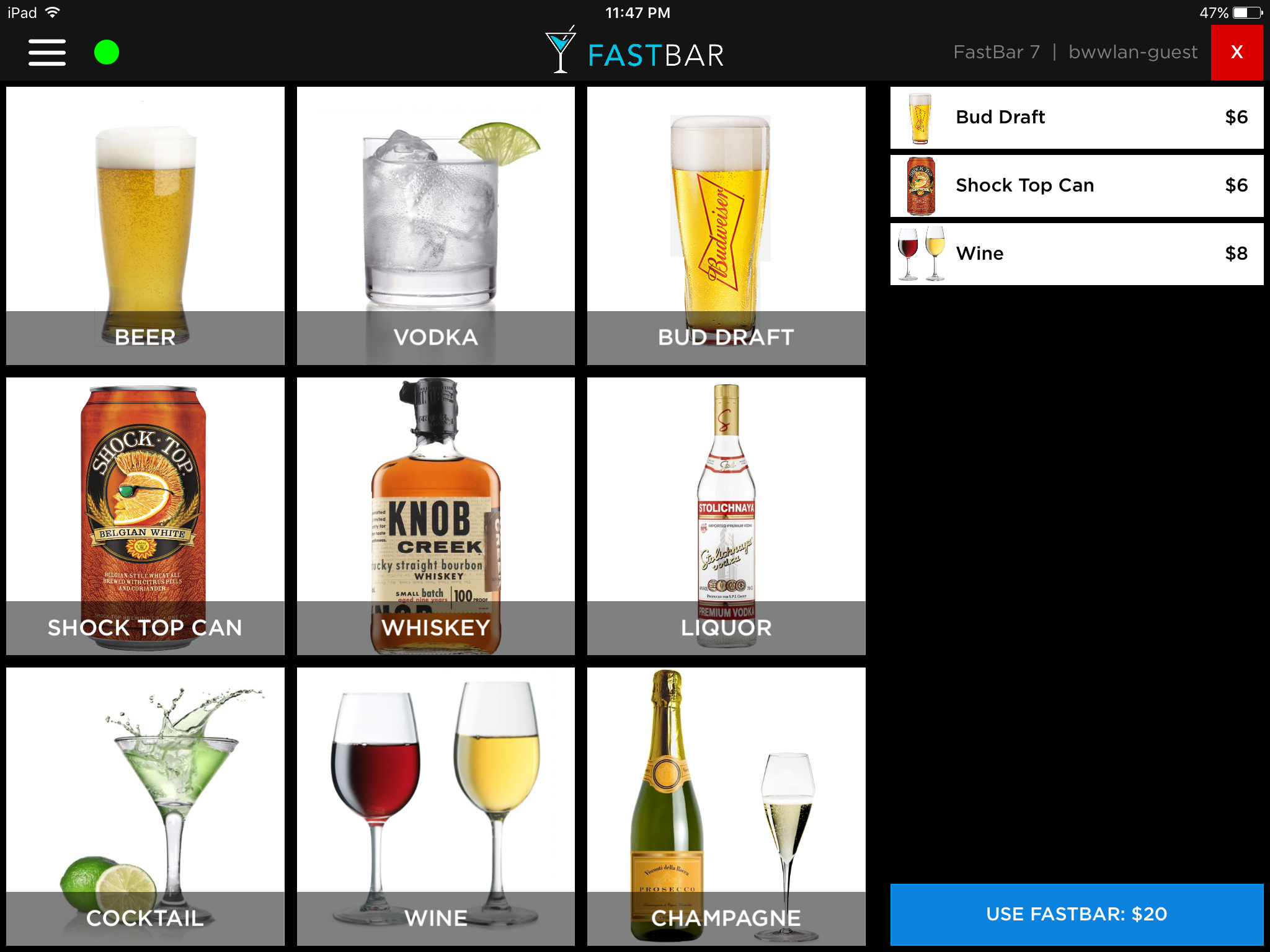

When I first started development on FastBar a cashless payment system for events, there were a few key criteria that drove my decisions for the overall architecture of the system.

Fundamentally, FastBar is a payment system designed specifically for event environments. Instead of using cash or drink tickets or clunky old credit card machines, events use FastBar instead.

There are 2 key characteristics of the environment in which FastBar operates, and the system that provide that drive almost all underlying aspects of the technical architecture: internet connectivity sucks, and we're dealing with people's money.

Internet connectivity at an event sucks

Prior to starting FastBar, I had a side business throwing events in Seattle. We'd throw summer parties, Halloween parties, New Year's Eve parties etc… In 10 years of throwing events, I cannot recall a single event where internet worked flawlessly. Most of the time it ranged from "entirely useless" to "ok some of the time".

At an event, there are typically 2 choices for getting internet connectivity:

Rely on the venue's in-house WiFi

Use the cellular network, for example a hotspot

Sometimes the venue's WiFi would work great in an initial walkthrough… and then 2000 people would arrive and connectivity goes to hell. Other times it would work great in certain areas of the venue, then we tested it where we wanted to setup registration, or place a bar, only to get an all too familiar response from the venue's IT folks: "oh, we didn’t think anyone would want internet there".

Relying on hotspots was just a bad: at many indoor locations, connectivity is poor. Even if you're outdoors with great connectivity, add a couple of thousand people to that space, each of them with smartphones hungry for bandwidth so they can post to Facebook/Instagram/Snapchat, or their phone just decides now is a great time to download that latest 3Gb iOS update in the background.

No matter what, internet connectivity at event environments is fundamentally poor and unreliable. This is something that isn't true in a standard retail environment like a coffee shop or hairdresser where you'd deploy a traditional point of sale, and it would have generally reliable internet connectivity.

We're dealing with people's money

For the event, the point of sale system is one of the most critical aspects - it effects attendee's ability to buy stuff, and the events ability to sell stuff. If the point of sale is down, attendees are pissed off and the event is losing money. Nobody wants that.

Food, beverage and merchandise sales are a huge source of revenue for events. For some events, it could be their only source of revenue.

In general, money is a very sensitive topic for people. Attendees have an expectation that they are charged accurately for the things they purchase, and events expect the sales numbers they see on their dashboard are correct, both of which are very reasonable expectations.

Reliability and Resiliency

Like any complicated, distributed software system, there are many non-functional requirements that are important to create something that works. A system needs to be:

Available

Secure

Maintainable

Performant

Scalable

And of course reliable

Ultimately, our customers (the events), and their customers (the attendees), want a system that is reliable and "just works". We achieve that kind of reliability by focusing on resiliency - we expect things will fail, and design a system that will handle those failures.

This means when thinking about our client side mobile apps, we expect the following:

Requests we make over the internet to our servers will fail, or will be slow. This could mean we have no internet connectivity at the time and can't event attempt to make a request to the server, or we have internet, but the request failed to get to the server, or the request made it to our server but the client didn't get the response

A device may run out of battery in the middle of an operation

A user may exit the app in the middle of an operation

A user may force close the app in the middle of an operation

The local SQLite database could get corrupt

Our server environment may be inaccessible

3rd party services our apps communicate with might be inaccessible

On the server side, we run on Azure and also depend on a handful of 3rd party services. While generally reliable, we can expect:

Problems connecting to our Web App or API

Unexpected CPU spikes on our Azure Web Apps that impact client connectivity and dramatically increase response time for requests

Web Apps having problems connecting to our underlying SQL Azure database or storage accounts

Requests to our storage account resources being throttled

3rd party services that normally respond in a couple of hundred milliseconds taking 120+ seconds to respond (that one caused a whole bunch of issues that still traumatize me to this day)

We've encountered every single one of these scenarios. Sometimes it seems like almost everything that can fail, has failed at some point, usually at the most inopportune time. That's not quite true, I can mentally create some nightmare scenarios that we could potentially encounter in the future, but these days we're in great shape to withstand multiple critical failures across different parts of our system and still retain the ability to take orders at the event, and have minimal impact to attendees and event staff.

We've done this by focusing on resiliency in all parts of the system - everything from the way we architect to the details of how we make network requests and interact with 3rd party services.

Processing an Order

To illustrate how we achieve resiliency, and therefore reliability, let's take a look at an example of processing and order. Conceptually, it looks like this:

The order gets created on the POS and makes an API request to send it to the server. Seems pretty easy, right?

Not quite.

Below is a highly summarized version of what actually happens when an order is placed, and how it flows through the system:

There is a lot more to it that just a simple request-response. Instead, it's a complicated series of asynchronous operations and a whole bunch of queues in between which help us provide a system that is reliable and resilient.

On the POS App

- The underlying Order object and associated set of OrderItems are created and persisted to our local SQLite database

- We create a work item and place it on a queue. In our case, we implement our own queue as a table inside the same SQLite database. Both steps 1 and 2 happen transactionally, so either all inserts succeed, or none succeed. All of this happens within milliseconds, as it's all local on the device and doesn't rely on any network connectivity. The user experience is never impacted in case of network connectivity issues

- We call the synchronization engine and ask it to push our changes

- If we're online at the time, the synchronization engine will pick up items from the queue that are available for processing, which could be just the 1 order we just created, or there could be many orders that have been queued and are waiting to be sent to the server. For example if we were offline and have just come back online. Each item will be processed in the order that it was placed on the queue, and each item involves its own set of work. In this case, we're attempting to push this order to our server via our server-side API. If the request to the server succeeds, we'll delete the work item from the queue, and update the local Order and OrderItems with some data that the server returns to us in the response. This all happens transactionally.

- If there is a failure at any point, for example a network error, or a server error, we'll put that item back on the queue for future processing

- If we're not online, the synchronization engine can't do anything, so it returns immediately, and will re-try in the future. This happens either via a timer that is syncing periodically, or after another order is created and a push is requested

- Whenever we make any request to the server that could update or create any data, we send a IndempotentOperationKey which the server uses to determine if the request has been processed already or not

The Server API

- Our Web API receives the request and processed it

- We make sure the user has permissions to perform this operation, and verify that we have not already processed a request with the same IdempotentOperationKey the client has supplied

- The incoming request is validated, and if we can, we'll create an Order and set of OrderItems and insert them into the database. At this point, our goal is to do the minimal work possible and leave the bulk of the processing to later

- We'll queue a work item for processing in the background

Order Processor WebJob

- Our Order Processor is implemented as an Azure WebJob and runs in the background, constantly looking at the queue for new work

- The Order Processor is responsible for the core logic when it comes to processing an order, for example, connecting the order to an attendee and their tab, applying any discounts or promotions that may be applicable for that attendee and re-calculating the attendee's tab

- Next, we want to notify the attendee of their purchase, typically by sending them an SMS. We queue up a work item to be handled by the Outbound SMS Processor

Outbound SMS Processor WebJob

- The Outbound SMS processor handles the composition and sending of SMS messages to our 3rd party service for delivery, in our case, Twilio

- We're done!

That's a lot of complexity for what seems like a simple thing. So why would we add all of these different components and queues? Basically, it’s necessary to have a reliable and resilient system that can handle a whole lot of failure and still keep going:

If our client has any kind of network issues connecting to the server

If our client app is killed in any way, for example, if the device runs out of battery, or if the OS decided to kill our app since we were moved to the background, or if the user force quits our app

If our server environment is totally unavailable

If our server environment is available but slow to respond, for example, due to cloud weirdness (a whole other topic), or our own inefficient database queries or any number of other reasons

If our server environment has transitory errors caused by problems connecting with dependent services, for example, Azure SQL or Azure storage queues returning connectivity errors

If our server environment has consistent errors, for example, if we pushed a new build to the server that had a bug in it

If 3rd party services we depend on are unavailable for any reason

If 3rd party services we depend on are running slow for any reason

Asynchronicity to the Max

You'll notice the above flow is highly asynchronous. Wherever we can queue something up and process it later, we will. This means we're never worried if whatever system we're talking to is operating normally or not. If it's alive and kicking, great, we'll get that work processed quickly. If not, no worries, it will process in the background at some point in the future. Under normal circumstances, you could expect an order to be created on the client and a text message received by the customer within seconds. But, it could take a lot longer if any part of the system is running slowly or down, and that's ok, since it doesn't dramatically affect the user experience, and the reliability of the system is rock solid. .

It's also worth noting that all of these operations are both logically asynchronous, and asynchronous at the code level wherever possible.

Logically asynchronous meaning instead of the POS order creation UI directly calling the server, or, on the server side, the request thread directly calling a 3rd party service to send an SMS, these operations get stored in a queue for later processing in the background. Being logically asynchronous is what gives us reliability and resiliency.

Asynchronous at the code level is different. This means that wherever possible, when we are doing any kind of I/O we utilize C#’s async programming features. It's important to note that underlying code being asynchronous doesn’t actually have anything to do with resiliency. Rather, it helps our components achieve higher throughput since they're not tying up resources like threads, network sockets, database connections, file handles etc… waiting for responses. Asynchronity at the code level is all about throughput and scalability.

Conclusion

When you're building mobile applications connected to the cloud, reliability is key. The way to achieve reliability is by focusing on resiliency. Expect that everything can and probably will fail, and design you system to handle these failures. Make sure your system is highly logically asynchronous and queue up work to be handled by background components wherever possible.